What do you truly want? And what would you give to find that?

What do you truly want? And what would you give to find that?

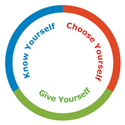

Emotional intelligence is a resource we all have, but it’s hard to use this capability without a process, a roadmap. In the Six Seconds Model of Emotional Intelligence, there are three “pursuits” forming a process framework that enables people to be more effective by tapping the power and wisdom of feelings. The first two pursuits are reasonably straightforward, albeit enormously challenging to accomplish consistently. The third is a paradox that many find contradictory… yet it’s what makes the model transformational. The first two are:

Know Yourself means tuning into our own feelings and behaviors, and seeing the links between our feelings, thoughts, and actions. This requires a mindfulness and compassionately honest self reflection that’s extremely rare in a fast-paced world.

Know Yourself means tuning into our own feelings and behaviors, and seeing the links between our feelings, thoughts, and actions. This requires a mindfulness and compassionately honest self reflection that’s extremely rare in a fast-paced world.

Choose Yourself means pausing to evaluate the data gathered from “Know Yourself,” and shifting from “reaction” to “response.” To show up intentionally requires a delicate balance of self-discipline and self-acceptance — being our real selves honestly, and also being better each day.

To some, the third pursuit sounds like weakness, but it’s actually the more powerful. It’s a kind of super-charger on the engine of the model — it moves Six Seconds EQ from “nice to have” to “need to have.” We call the third pursuit “Give Yourself,” and it’s about serving your purpose. In the first two pursuits, we build awareness and then create intentional responses. But what are we using that awareness and intention for?

In Give Yourself we ensure our steps are actually going someplace worthwhile. It’s about connecting with others and the larger world, finding unique purpose and serving it.

In Give Yourself we ensure our steps are actually going someplace worthwhile. It’s about connecting with others and the larger world, finding unique purpose and serving it.

Sometimes people react to the term “Give Yourself” because it might sound “too nice,” but actually it’s an intensely practical process. The reality is that without this, we rarely get what we want; we wear armor that is an illusion of protection that only serves to isolate us. Give Yourself is the way we get what we actually want instead of simply exercising the hedonic treadmill, endlessly pouring our lives into a bottomless pit of self-gratification or chasing external validation.

The central paradox is that when we are “taking” and “protecting” or even “striving” and “winning,” we usually get the opposite of what we truly want; but when we give, we get. This principle defies the carefully constructed economists logic used to drive markets and industries and nations vying for dominance — yet it’s no less true. When we’re focused on taking, we never have enough, we are never enough, and we are profoundly alone. When we are giving there is abundance, we are more than enough (which is why we can give), and we are deeply connected.

Seth Godin recently wrote about this paradox and how the web actually amplifies the results of “Giving Yourself” (and of taking) — he calls Philanthropists the ones who give more, and Bandits the ones who take more:

The fascinating thing for me is how much more successful and happy the philanthropists are. It turns out that when you make the world smaller, you get to keep more of what you’ve got, but you end up earning a lot less (respect, connections, revenue) at the same time.

Does this match your experience? Are those who focus on taking for themselves, in the end, less connected, less whole, less happy? Does the attitude and action of genuine giving somehow unlock a sense of belonging and feeling of place in a larger world?

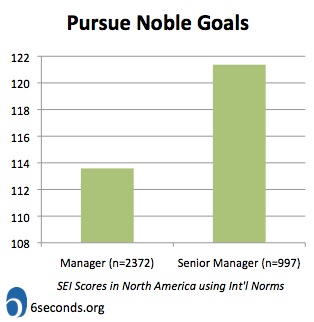

If that’s not enough, it turns our this commitment will also get you ahead in your career. New research we’re analyzing now, looking at over 27,000 individuals globally in terms of emotional intelligence scores: Generally, more senior leaders have higher EQ (this is not a surprise since EQ is predictive of career success — hired for IQ, promoted for EQ). The surprise, perhaps, is that the single EQ competency with the greatest gap is in Give Yourself, specifically the capability to Pursue Noble Goals. In fact, those in the top band of the competency are almost twice as likely to be in the most senior organizational roles.

If that’s not enough, it turns our this commitment will also get you ahead in your career. New research we’re analyzing now, looking at over 27,000 individuals globally in terms of emotional intelligence scores: Generally, more senior leaders have higher EQ (this is not a surprise since EQ is predictive of career success — hired for IQ, promoted for EQ). The surprise, perhaps, is that the single EQ competency with the greatest gap is in Give Yourself, specifically the capability to Pursue Noble Goals. In fact, those in the top band of the competency are almost twice as likely to be in the most senior organizational roles.

There is an element of giving that’s about generosity, an element about self-fulfillment… there is also a significant component of empathy. When we emotionally connect with others, we recognize a fundamental shared humanity — we know we’re all in the same lifeboat. It’s this connection that links giving to both happiness and performance.

In a fascinating TED talk (video is below), Michael Norton discusses a number of studies on the finance of happiness. You CAN buy happiness, he asserts — it’s just not the type of transaction most of us imagine when we here that phrase. The paradox of giving.

While many people will accept this “give to get” notion in their private lives (or at least in a church/temple/mosque), it seems to be a huge leap for modern entrepreneurs to see the value. Yet some companies attract and retain great talent because their work matters. Others have created a culture of mutual win that supports excellence — in Norton’s research, when an individual is given a €15 incentive for himself, the company generates €4.5 in value (a lost of over €10)… but when he’s given €15 to give to the benefit of others, the company returns a massive €78 in value (a 520% ROI). Imagine creating a climate of giving in your company — a culture where people genuinely, spontaneously, and regularly exercise generosity!

Finally, in another forthcoming White Paper, we did a study of private bankers. One might expect those who are financially driven and focused on their own success to make the most. But again, the EQ competency of Pursue Noble Goals proves to be a strong predictor of the total wealth each banker has under her/his management. Those in the group with the largest investment funds have over 30% higher scores on “Pursue Noble Goals” than their lower-performing colleagues. The higher performers also showed nearly 25% higher scores on the self-awareness skill we call “Recognize Patterns.”

Those who give of themselves, those who serve a compelling purpose, are happier and are more often in senior positions. They motivate others and build economic as well as social value. So how do we integrate that into our lives? Do we need to accumulate wealth so we can give it? While people and companies frequently say they need to “do well in order to do good,” it turns out that actual abundance is probably not the source of giving.

Those who give of themselves, those who serve a compelling purpose, are happier and are more often in senior positions. They motivate others and build economic as well as social value. So how do we integrate that into our lives? Do we need to accumulate wealth so we can give it? While people and companies frequently say they need to “do well in order to do good,” it turns out that actual abundance is probably not the source of giving.

While we might expect those who are well off to be more empathic and generous, some research suggests the opposite. It is true that very wealthy give extensively (and the largest philanthropic donations do come from some fabulously wealthy patrons) there are many studies indicating that in proportion to their means, those with less actually give more.

What, then, is required? Having more doesn’t seem to be the answer — instead we need to teach people to connect to their own and others’ emotions. What awareness and skills can we build that allow people to transcend ego and connect with their larger vision? And, especially to do so when they’re in times of stress and challenge? Perhaps one reason the Six Seconds Model is so powerful is that it provides a process to shift toward this way of engaging — to align what we’re doing and how we’re responding to our own most significant goals.

***