Part One introduced the importance of emotional intelligence, and Part Two focused on understanding emotions and patterns (our typical reactions). Now Part Three of this series explores how we can make a choice to respond rather than reacting.

My kids, Emma and Max, have had the same argument about 7 million times. It goes about like this:

- They’re playing and having a great time.

- Max starts getting a little bored or rebellious so Emma tries to control the game to make it more fun. He feels a bit squished by this, and acts out a little more.

- Emma doesn’t like the way he’s messing around, and so she gets fiercer about the rules… and he gets more rebellious.

- They explode, and eventually end up in time out.

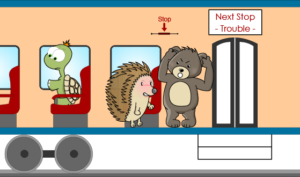

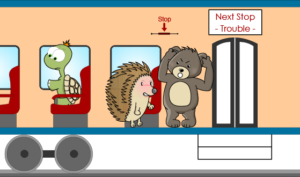

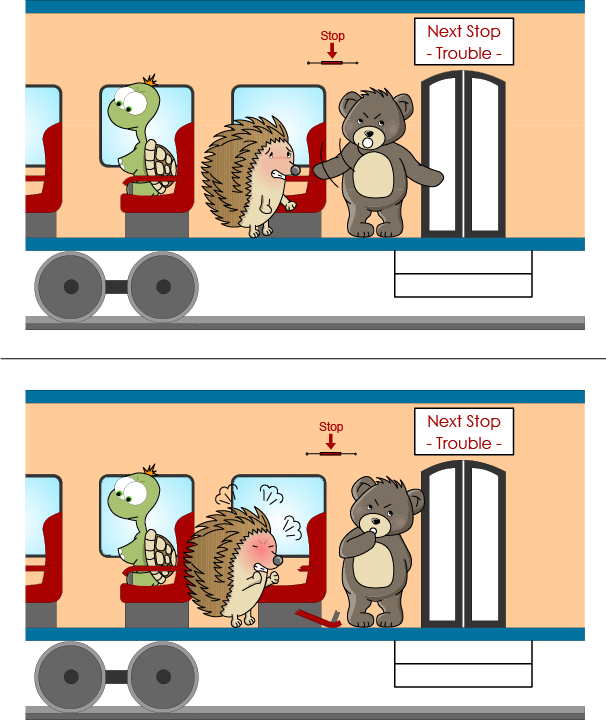

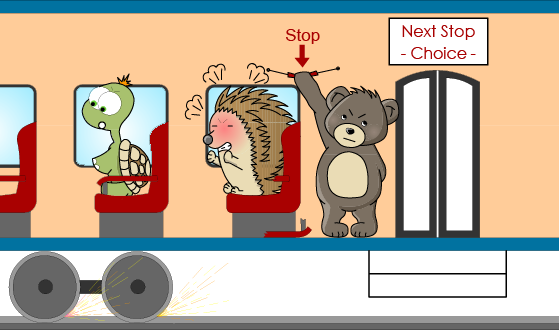

Around step 2, it’s obvious (to me and their mom) that they are headed toward the explosion. The momentum builds up and they both get more and more reactive. The tension builds. Like a train going faster, their fight gets going stronger and stronger. The longer it continues, it becomes harder and harder for them to “get off the train.”

I call this kind of situation a Trouble Train — it comes from following patterns that lead to a bigger mess. The “trouble” could be time out or other consequence, or a fight, or even something more serious like stealing or hurting people or breaking something. The “trouble” could also happen inside someone, like a deep sadness or volcano of anger turned against yourself. Some Trouble Trains lead to hurt and sorrow, some lead to conflict, some lead to loneliness. Some Trouble Trains are worse, they could lead to violence, or danger, or jail, or being kicked off a team. While we can learn from these experiences, it would certainly be more pleasant to get off the train before it arrives at these destinations.

Have you ever found yourself in the middle a situation and you know it will to turn into a big mess? You can feel it slipping out of control… and yet you keep going. It’s as if you’re being pushed along this track; you know it’s going to lead to trouble, but it seems like there’s no choice.

What’s it like for you when that happens? What is the trouble to which it leads you?

Or have you noticed that you often have the same kind of challenges over and over? Maybe you have an argument with your brother or sister or friend… and you can see that same fight happens a lot?

When you’re in those situations, you are on the Trouble Train.

You can tell it’s a Trouble Train when:

- You’ve been on this pathway before – your patterns of reacting are part of the fuel.

- The situation will result in a consequence that you don’t want.

Next Stop: Trouble

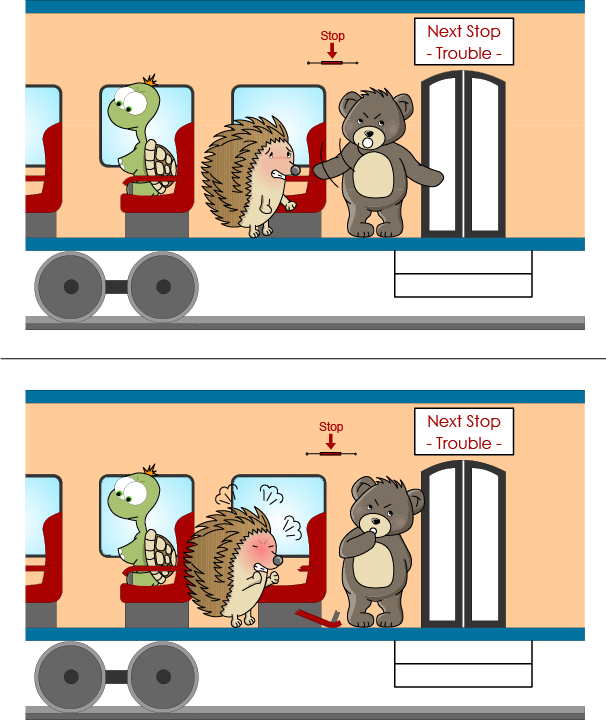

Recently Emma and Max were on their usual Trouble Train, and I stopped them and asked: “Do you notice you’re on a Trouble Train?” “NO,” growled Emma fiercely trying to get back to her argument. She was so focused on being right and “winning” the argument, she wasn’t noticing her reaction.

I can relate to this. When I’m on the Trouble Train, I find it difficult to get off. There seems to be a part of me that WANTS to keep the fight going. For example, sometimes I have an argument with my wife and while I know it’s not making life better, I find myself saying just one more point. Or sometimes I feel hurt and I want to hurt her back. I’ve noticed the longer I am on the train, the harder it is to stop. The energy builds up and up, and my feelings get more and more complicated.

So, an obvious solution is to stop the train fast. When the reaction is just getting started the situation is not so intense.

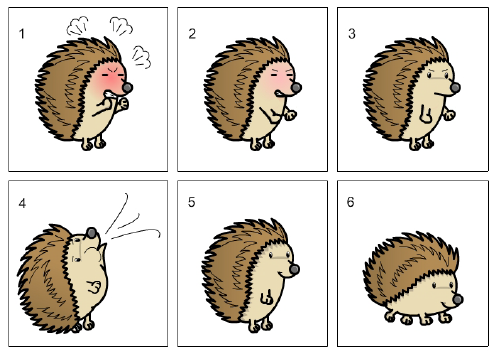

Remember in the article “Decoding Emotions” where I wrote about patterns? For example, maybe my pattern is: When I feel hurt, I want to hurt the other person. That one is a “Trouble Train” pattern for me, because when I follow the pattern I definitely get a consequence that I dislike.

When we know our patterns, it’s easier to notice and solve the problem BEFORE the train gets going fast.

Sometimes I feel a little hurt, then start getting a little argumentative. The other person says something a bit harsher, and I say something back that’s a little mean. They come back with something even meaner, and I want to hit them, but instead I say something really hurtful. Pretty soon we’re both hurt and angry, and it’s really hard to work out the problem.

In those times, I probably am ignoring my own feelings. I feel a little hurt, but I don’t pay attention to that important message, and so I push ahead. Fortunately, I’ve learned that I have this pattern and I’ve come to recognize that it’s a Trouble Train. So now, sometimes, when I notice myself feeling a little hurt and wanting a little revenge, I can say, “Hey! This is NOT the train I want to take…”

If I notice when I feel just a tiny bit hurt, I can choose a different train. I could solve the problem pretty easily by having a calm conversation, such as:

“When you said ____, I felt hurt. Did you mean to hurt my feelings? Maybe we can take a break and talk about this in a friendly way in a few minutes?”

Remember, just like real trains, Trouble Trains get going faster as you ride them longer. So: The sooner I can notice that I’m on a Trouble Train, the easier it will be to get off!

How about you?

Is it hard for you to notice yourself on a Trouble Train?

What feelings “push” you onto a Trouble Train?

What feelings make the train go even faster?

If you could avoid getting on your Trouble Train, how would that help you?

Good news! By carefully noticing your feelings when they’re small, you can discover a wonderful secret:: You do not have to get on the Trouble Train.

However, even if you do get on, there’s still hope. You can stop the train before you reach real trouble.

–

–

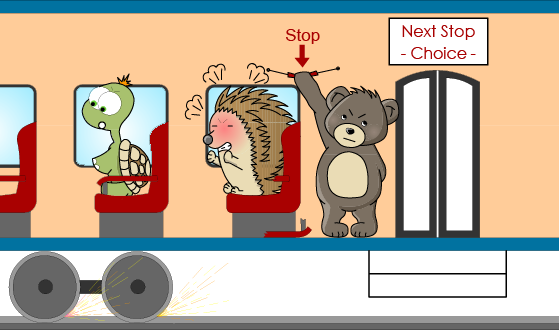

Next Stop: Choice

Ideally, you notice your feelings and patterns before the train even gets going, but sometimes we all get on the train. There’s some good news:

You don’t have to stay on the Trouble Train!

The first step is to notice you’re on that train again. Then, once you notice you’re on a Trouble Train, what can you do?

As I said, part of you might want to keep it going, but part of you might want to get off. Just KNOWING that you have a choice is a powerful tool. There’s a skill called Exercising Optimism that helps this. If you are feeling helpless and hopeless, you might not believe that you have any choice. In those times, it’s useful to remember that many times in the past you have been in difficult situations and found your way through. Also, since nothing lasts forever, this situation will change too. Maybe you can’t fix everything, but what is SOMETHING you can do? What is one small step you could take?

As I said, part of you might want to keep it going, but part of you might want to get off. Just KNOWING that you have a choice is a powerful tool. There’s a skill called Exercising Optimism that helps this. If you are feeling helpless and hopeless, you might not believe that you have any choice. In those times, it’s useful to remember that many times in the past you have been in difficult situations and found your way through. Also, since nothing lasts forever, this situation will change too. Maybe you can’t fix everything, but what is SOMETHING you can do? What is one small step you could take?

It can also be extra complicated in a situation with other people. Maybe you want to stop the train, but they are still pushing it forward. Sometimes when you try to make them stop, the situation seems to get worse, so instead of trying to stop the whole thing, just get yourself off. When you take responsibility for your own choices, that can make it much easier for others to do the same.

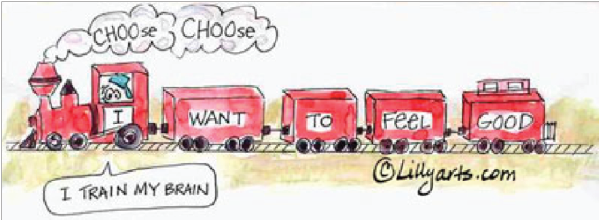

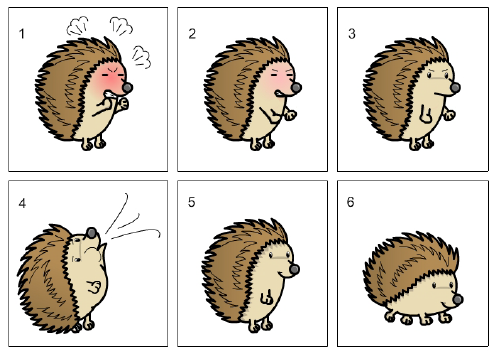

One tool for getting off the train is called the Six Second Pause. The purpose is to slow down your reaction and let the emotional energy relax a moment. It works because the chemicals of emotion inside our brains and bodies only last about six seconds. Normally when we have strong feelings, we keep producing more and more of the feeling molecules. But if we can stop for a short moment, the flood of chemicals slows down. The trick with a Six Second Pause is to refocus your brain by shifting attention from the emotional part (the “limbic brain”) to the analytical part of your brain (called the “Cortex”). Your Cortex loves to put ideas in order, break ideas apart, and to use symbols like math or language. So, invite your Cortex to the party by doing things it likes, such as:

Solve six math problems.

Remember six words in a foreign language.

Put six favorite songs in alphabetical order.

List six TV characters.

…

Another key to stopping the train is the fact that you have multiple emotions. I wrote about this in the previous chapter. Maybe you feel sad and worried and mad and those feelings are big – they’re taking center stage right in the spotlight. At the very same time, maybe you feel caring and committed, but those feelings are hiding in the background. Bring them into the light! Don’t let a few of your feelings run the show, invite the others to join.

For example, maybe you are sad about a friend leaving town. Do you have any other feelings? How about happy to have such a good friend? Worried about if you’re going to stay close? Excited about when you’ll see them again?

Simply recognizing that you have these other feelings can begin to change your emotions. You can intensify the more constructive or useful feelings by naming them, and remembering why you have those feelings. You can intensify any feeling by focusing on it.

Try this! See if you can change your feelings just by focusing on them.

Think of situation where you were annoyed. Remember the annoying details and see if you can feel more annoyed.

Now, this of something funny, and focus on that. See if you can feel more of that silly feeling.

How about sad? Worried? Curious? Happy?

See? You can change your feelings!

–

–

Less Fuel

In an old-fashioned steam train, when you shovel more coal into the fire, the train runs faster. What thoughts, feelings, and actions fuel your Trouble Train? You can slow the train by adding opposite thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Here are other techniques for reducing the intensity of the fire:

Heart Breathing: Breathe slowly in counting six full seconds, then breathe out completely over another slow six second count. As you are breathing, focus your attention on your heart, and imagine your heart slowing to a calm beat.

Glow: Imagine yourself filling up with cool, beautiful light. Imagine the light flowing out your fingers.

Warm Layers of Feelings: You might be irritated or hurt or impatient AND underneath that you might have other feelings that are warm and gentle. Notice those gentle feelings and focus on them to make them stronger.

Cotton Candy: Imagine your feelings are like wisps of energy around your body. Imagine scooping up the wisps like they are cotton candy and squeezing them into a yummy treat you can enjoy.

Shrinking: Name your feelings and give them a score from 0 (not present) to 10 (overwhelmingly strong). Imagine these feelings as a ball – imagine the shape, size, and color (e.g., maybe you’re angry and scared, it’s an 8 in intensity, and you imagine a spiky black and red ball as big as a house). Breathe slowly in and out, and each time you breathe out, imagine your breath cooling the ball causing it to get a little smaller and lighter in color. Imagine this for 30 seconds. Now how intense are the feelings?

–

–

Staying Off

One of the best ways to solve the Trouble Train problem is to stay off in the first place! There are always disappointments, differences of opinion, and challenges that could put you on the train, but there are other ways of responding.

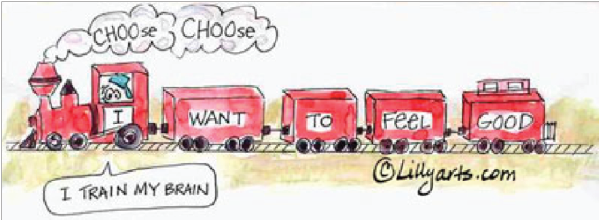

If you know your usual Trouble Train (or Trains!!) then it will be easier to avoid them. Maybe you can find a different train that goes someplace more fun?

For example, suppose you have a pattern “When I feel bored, I act annoying to get attention,” and this leads you to a Trouble Train. The moment you begin to feel a little bored, consider: Is there another train I could choose to take? Not because someone else is “making me,” but because I want to?

Could I connect with someone? Amuse myself? Learn something new? Do some exercise? Read? Draw? Write?

What might happen next?

cartoon used with permission from lillyarts.com

.::.

©2011 Joshua Freedman, Six Seconds (www.6seconds.org). All Rights Reserved. Illustrations by Logoxid.

Thank you to Emma and Max for being patient about my sharing their “Trouble Train” challenges and for their ideas in the “less fuel” section.

.::.

As I said, part of you might want to keep it going, but part of you might want to get off. Just KNOWING that you have a choice is a powerful tool. There’s a skill called Exercising Optimism that helps this. If you are feeling helpless and hopeless, you might not believe that you have any choice. In those times, it’s useful to remember that many times in the past you have been in difficult situations and found your way through. Also, since nothing lasts forever, this situation will change too. Maybe you can’t fix everything, but what is SOMETHING you can do? What is one small step you could take?

As I said, part of you might want to keep it going, but part of you might want to get off. Just KNOWING that you have a choice is a powerful tool. There’s a skill called Exercising Optimism that helps this. If you are feeling helpless and hopeless, you might not believe that you have any choice. In those times, it’s useful to remember that many times in the past you have been in difficult situations and found your way through. Also, since nothing lasts forever, this situation will change too. Maybe you can’t fix everything, but what is SOMETHING you can do? What is one small step you could take?

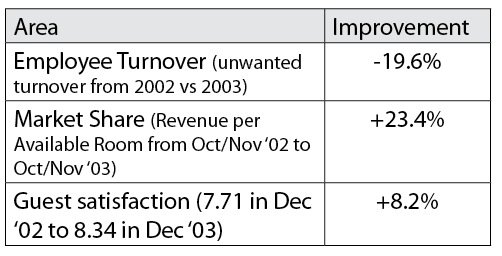

In December, 2002, a new General Manager was taking over the Sheraton Studio City Hotel to increase profitability in the 302 room / 592 bed property. Changes in the Orlando tourist market and numerous management changes over the previous years created a unique set of challenges. Guest satisfaction scores were not at an acceptable level, sales were off, morale was low, and departments were not working together smoothly. In the General Manager’s view, “We struggled to focus on the necessary changes, but territorial struggles and low morale seemed intractable. We had difficulty even framing many of the issues.” The new General Manager, Grant Bannen, and his HR Director, Catherine Melnyk, invited a proposal from Six Seconds to assist with the turnaround.

In December, 2002, a new General Manager was taking over the Sheraton Studio City Hotel to increase profitability in the 302 room / 592 bed property. Changes in the Orlando tourist market and numerous management changes over the previous years created a unique set of challenges. Guest satisfaction scores were not at an acceptable level, sales were off, morale was low, and departments were not working together smoothly. In the General Manager’s view, “We struggled to focus on the necessary changes, but territorial struggles and low morale seemed intractable. We had difficulty even framing many of the issues.” The new General Manager, Grant Bannen, and his HR Director, Catherine Melnyk, invited a proposal from Six Seconds to assist with the turnaround. Among other topics, the teams were taught an introduction to emotional intelligence, the Six Second Pause to manage reactions, Conditions of Satisfaction to increase accountability, a model for intrinsic motivation, and Emotional Awareness for improving employee and guest interactions. The sessions emphasized the importance and value of emotions both for interfacing as a team, with employees, and with guests. A consistent theme of the trainings was “Quality Comes from the Inside” under the premise that our internal state of affairs ultimately translates to how we deal with customers. Using Six Seconds learning design, the majority of the trainings focused on experiential learning leading to meaningful dialogue and reflection.

Among other topics, the teams were taught an introduction to emotional intelligence, the Six Second Pause to manage reactions, Conditions of Satisfaction to increase accountability, a model for intrinsic motivation, and Emotional Awareness for improving employee and guest interactions. The sessions emphasized the importance and value of emotions both for interfacing as a team, with employees, and with guests. A consistent theme of the trainings was “Quality Comes from the Inside” under the premise that our internal state of affairs ultimately translates to how we deal with customers. Using Six Seconds learning design, the majority of the trainings focused on experiential learning leading to meaningful dialogue and reflection.